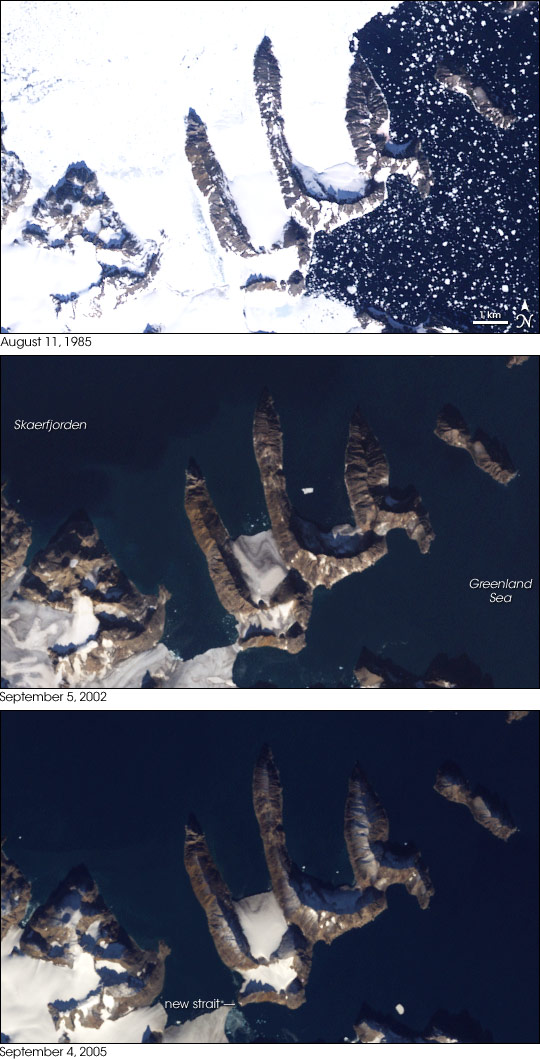

Related to my first post, here is a news story that is a bit dated now, but I find is still relevant. In this case the Greenland ice cap was not only hiding mountains, but the existence of islands that no one knew even existed. Could the largest island in the world actually be just an agglomeration of multiple distinct islands?

Melting Ice Reveals New Island off Greenland

Then again, remember it is still just a matter of perspective. The island revealed in this photo is obviously part of the same mountain range that was thought to be continuous, except in this case, instead of being connected under ice, it is connected under water. The ice is just one layer of the topographic onion. If you remove the water, then the further analysis of topography can continue.

The Earth's surface can roughly be divided into two categories: Ocean Floors and Continent Land Masses. While it would be tempting to distinguish them by the simple presence of water, that would not only be incorrect but also be attributing water to the reason for a difference. The rocks of these two types of land have different chemical compositions, physical attributes and geologic history. It is these concrete differences that results in one being mostly under water and one not, though in fact there are many cases where the ocean floor is exposed above water (Iceland being the most famous example) and where the continental land mass is under water.

Most maps today show the borders of continents to be where the current coast line is, rather than the boundary where continent meets ocean floor. The reason for this is that the oceans have flooded large parts of our continents creating shallow seas. The parts of the continent that are flooded are what we call continental shelves.

This map shows the continents with the continental shelves visible in light blue:

While Greenland is a continental land mass and is most certainly surrounded by water, it does not rise from ocean floor and is not its own continental land mass. As this map shows, it is in fact part of the North American continent.

This makes us beg the question: What is the true definition of an island? In Bali there is a famous Hindu temple that is only accessible by a land bridge at low tide. In Europe there are myriads of castles that are in a similar position. In Maine there are many summer homes that momentarily become islands with the flow of tides. Are these truly islands though? A home owner might like the cachet of saying s/he owns a private island, but it would be a rather dubious claim.

Then again, no one doubts that Greenland is an island. But, in the grand scheme of earth’s geologic time (4.6 billion years and counting), the ebb and flow of tidal waters are not that different from the rising and falling of global sea levels. Instead of rowing over them, there have been many times when it would have been possible to walk up and down the ridges and the valleys of the current continental shelf from Canada to Greenland. The presence of deep canyons eroded by rivers that once flowed to the edge of the continent provide clear proof that this land was once above the sea level.

By peeling away the ocean layer of the onion one can realize how the boundaries we apply to our visualization of the Earth are often just arbitrary and one of many possible options. The melting of glaciers might provide for new surprises in the future (including hermetically sealed liquid lakes kilometers under the Antarctic Ice) but that very melting is causing global ocean levels to rise thereby further shrouding complex topographies under a flat water line.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Nunataks

Chances are slim that you will find yourself on a stroll in eastern Greenland. After all, it is a bleak cold landscape covered by an ice sheet. In fact, this ice sheet is so thick that you would be strolling at high elevation and be further hampered by thin air.

If you did just happen to be plucked down there though, the only features you could use to orient yourself would be occasional rocky outcrops that protrude above the ice line and provide a relief against the white monotony.

These protrusions, some as small as boulders, are called nunataks and provide just a hint of what is under the ice you would be walking on: whole mountains kilometers high.

The concept of the nunatak is not that different from the "tip the iceberg.” In this case, however, the “tip” is part of a large, interconnected mountain range, and the “ice” is the enveloping medium. Yet, given the difference in scale, it is ironic that more is probably known about icebergs than these mountain ranges. You can go online these days to get live positioning of icebergs, but if you look at a map of Greenland today all it shows is ice, rather than the actual geologic features of the earth.

View Larger Map

Don’t you want to know what the features of the largest island on the planet are?

I guess there are practical considerations to displaying the topography as ice though. After all, if you do take that stroll there, you will be walking above the valleys and ridges not trudging up and down them. Furthermore, from a hazard point of view, none of these mountains will sink a Titanic or clip an airplane. Nonetheless, the fact that there are very solid shapes and spaces under the ice provides an alluring mystery, and, as a concept, is a good starting point for this blog.

In this blog I intend to write loosely about 3 topics, and in the process hopefully increase you appreciation of geology:

1. The aesthetic allure of topographies

2. The relativistic nature of comprehending and internalizing these topographies.

3. The processes and timescales involved in the their creation

Of course, it is hard to talk about one of these points without addressing the other. If topography is often not just in the eye of the beholder, but in the mind of the beholder, how can one have a meaningful aesthetic discussion?

In the not-so-subtle example of Greenland, one person might view the topography as ice littered with boulders, another might erase the ephemeral ice from the picture and focus on the erstwhile hidden solid mountainous landscape of the island, whilst a third might erase the mountains from the picture and be interested in seeing the flow, shape and relief of the ice sheet in isolation, as if it were a cast or mold. (In this case, the nanatucks would simply be holes in the ice leading to vast chambers).

While not so obvious, there are countless examples of “hidden” topography on earth (and surely other planets) that bare similar interest. In exploring them, we can also delve into the interesting geologic processes that created them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)